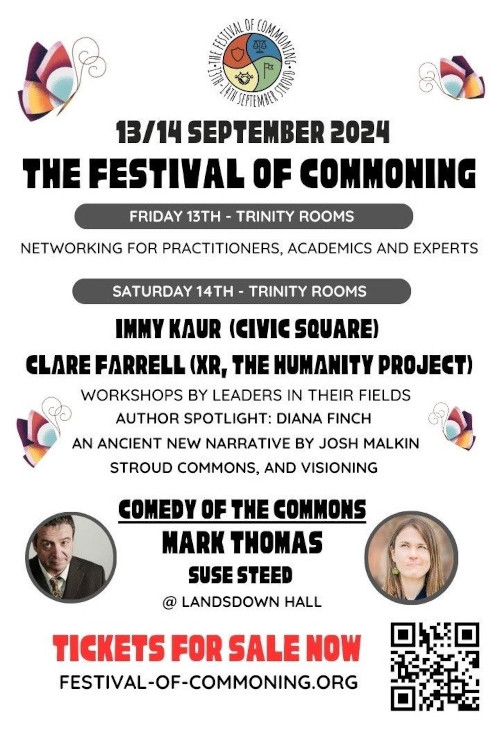

So, the first ‘Festival of Commoning’ happened in Stroud on Sep 13 & 14. This is a short report from one festival-goer, Dr Laura James. Next week, we’ll post a round-up by festival organisers, with thoughts, invitations for next year, more images and videos of presentations.

Earlier in September I was in Stroud, for the first Festival of Commoning. It was a lovely event, full of people working on commons projects in different ways.

What is a commons? It’s infrastructure for a basic, decent existence, operated and owned outside the market, locally governed and managed by multiple stakeholders. (we also heard a ‘more modern’ definition from the work of David Bollier and others – “a pervasive, generative, and neglected social lifeform… complex, adaptive living processes that generate wealth (both tangible and intangible) through which people address their shared needs with minimal or no reliance on markets or states.”). As well as actual commons, there were quite a few commons-adjacent projects discussed at the Festival.

The festival focussed on commoning, though, because whilst folks can light up when you say ‘commons’, a lot of people also instantly think of the tragedy of the commons – an unhelpful fallacy. We had the Comedy of the Commons instead on Saturday night, with Mark Thomas and Suse Steed, who were superb. Someone noted that the real tragedy is privatisation; or that our thinking has become enclosed, and so few people are aware that we can own and operate things differently.

There were quite a few talks, and also some time using liberating structures.

The classic commons reference is of course Ostrom, but a couple of people noted that her work was in an era where the people in a commons were more likely to be similar, whereas today in many commons settings, there will be a greater diversity of views, backgrounds, educations, etc. (Chik’s work is particularly focussed on this topic, finding ways to understand and connect with others who have very different perspectives.) A proper commons can’t be reabsorbed into capitalism – unlike some coops and mutuals in recent years. “If you sell shares or take on debt, you won’t be in the commons for long” – but there were interesting ideas for how to fund infrastructure without debt, such as selling vouchers at a discount for future energy (in kWh) or housing (in sqm) or care (hours).

We heard about a lot of different commons – energy, water, housing, care, cultural hubs, climbing gyms, food, land…

The local nature of such commons is helpful as you can have intersections between water, hydropower, heritage, sewage treatment, ecology and so on. Local connections can also help support rapid acquisition and transfer of assets into community ownership – if an opportunity comes up to buy some land with limited time, for instance, you don’t want to have to set up a new legal entity to buy it. (A couple of people referred to the capability to transvest things across into commons, although I’m not sure that’s a widespread term.)

Commons are easier to set up when there’s some existing sense of community; perhaps harder in some urban settings. Maybe crises are useful to catalyse new commons – but then it can also be too late. Commons run by volunteers can suffer the usual challenges of voluntary efforts – the risk of burning out those who do a lot for instance – and finding ways to pay for stewardship is really useful.

Dave Darby kicked off the Saturday with great enthusiasm – “own it together, make it affordable, keep it forever.” Part of the affordability can come from not needing to repay loan interest, so it can be cheaper to operate a commons asset. He was optimistic that there are now tools to bring together folks who are moving infrastructure into community ownership, and that commons can help individuals and communities avoid banks, debt, and privatisation. He mentioned projects (such as Liverpool’s Local Loop, from Mutual Credit Services – doing local credit clearing trading loops) and useful structural tools such as asset locks.

Diana Finch gave a very reflective talk on what happened with the Bristol Pound (sadly not enough to shift the dial locally, and not much impact on a macro scale). How can local money ideas – that would build community wealth, plus reduce carbon emissions – spread to the “non-woke mainstream”? Nudge economics is a lie, so it needs something more (we need individual, social and material change to change behaviour). How do we get a corporate lawyer to switch from driving their Tesla, to taking the bus? How can we make it cooler to say “I’m a bit late because we had to get a wheelchair off the 49 bus” than “I’m late because I had to charge my Tesla”? So they came up with Bristol Pay, which would take forward what they have learned, and also walk the fine line between enabling experiential learning, and avoiding manipulation and control of people. The plan was to operate at scale, and sneak in the real experiment as a kind of game. Bristol Pay was designed around tokens, which could optionally degrade over time. I liked the idea of tokens for reuse, where a drill (say) which was loaned out or gifted, would accrue tokens as it was used, and you could see which drills were particularly well utilised. (A drill is used on average for 4 minutes, before ending up in landfill.) Sadly it’s hard to get this sort of project going. Funders aren’t interested (philanthropic ideas of suitable beneficiaries don’t align); tokens get mixed up with blockchain/DAO ideas that are very tech heavy and have challenges around maintenance, power, disagreements. Finally it’s hard for people to understand how this sort of thing might be; we are so socialised into the idea of money. Even by age five, kids cannot imagine a world without money. So the cognitive dissonance when you think of these ideas is huge.

Immy Kaur was another amazing speaker, covering the journey of ImpactHub in Birmingham, through to Civic Square now. “What if the climate and ecological transition and deep retrofit of our homes and streets were designed, owned and governed by the people who live there?” ImpactHub was a crowdfunded space, and a trojan horse – looked like a creative coworking space with a beautifully designed front end, a safe unthreatening place for the city and donors. But they were organising, building capabilities and capacities, beyond the extractive system, creating new stories and surfacing others about relationships to each other, to land, to materials and economic ideas. They learned the power of infrastructure in building solidarity and motivating movement beyond the space. This was important, as it was shocking how all the lovely community halls, repair cafes, libraries etc were struggling, undervalued, fighting for money. It was a realisation that the basics can go backwards, not just getting better. And so more transformational change was needed, some way for civic and social infrastructure to be funded and supported so that it can thrive and survive, not be “wired for extraction” in a system which can only value finance. Indy Johar knew from the start that the ImpactHub would fail, but said it had to be done anyway. So from the start they published everything, worked in the open, so that others could see it. And be radicalised by it. And they did good work, improved the area, so their rent went up and up… The site didn’t sustain but the people did. Dark Matter Labs does projects which are starting to build the rewiring needed, to shift the systems such as land ownership. Civic Square is more the local practice, building the neighbourhood public square, with doughnut economics in mind (as we are both overshooting ecologically, and not delivering what local people need. So, things like both saving libraries as statutory services and reimagining them to be what we need in the future, probably a future which has a global increase of 3C, which for Birmingham would be 8C more in the summer. Today’s material economics don’t work.

Immy noted that they work across three matters – Dream, Dark, and Everyday. Everyday is the rhythm and ritual; the Dark is the hidden wiring of unjust systems that need dismantling; Dream is where we ignite radical imagination, to get beyond our current realities.

Claire Farrell from the Humanity Project talked about supporting different kinds of assembly in the UK, and the balance of not being too political, but also having some political understanding. A lot of political organising is boring, not fun…. but the right wing is adopting movement building tactics, and whipping up hatred. (And they know that media readers have low education and literacy levels, and that if they get the left onto big abstract topics then the left are doomed!) And the climate movement doesn’t always manage to cross class or race boundaries, and needs to build bridges. So the Humanity Project is trying to create a sense of possibility in a space where people are not being heard, by using assemblies, to intentionally build relationships across issues, and meet people where they are at, including people who are not like us or that we don’t like, or who think the queen was a lizard. Assemblies need to strike a balance between open space and specific topics, and so they do a community listening campaign (door knocking!) to find out what topics are hot, and then call an assembly about that. They are still learning what works well. Jo talked about a standing citizens assembly, there all the time, ready for use, and upweighting those who are most affected by a specific issue.

She also noted that the offence of public nuisance was originally a law to use against a company that was, say, causing pollution in a community; the application of this to today’s climate protesters is a real flip. Locating power you can do a jujitsu move on is the toughest thing; land commons is a great one to do. A bit of rewilding isn’t enough. Gandhi encouraging individuals to weave at home was both a symbolic act and a constructive one.

Chikara Shimasaki talked about setting up a commons climbing gym. The initial capital would be sourced from people buying prepaid vouchers for one off, monthly or annual gym passes. They did some great work, including getting the UK’s first insurer approval for an unstaffed, keycard access bouldering gym. The model will be lower price than for-profit gyms. Interestingly, local gyms don’t see it as competitive, but perhaps complementary – a gym that opens up new communities getting into the sport.

Dil Green has written a long piece introducing how housing commons could tackle the housing crisis. It’s not a completely straightforward idea to grasp, but it’s interesting to see how different aspects should make it work for people in different housing situations. There’s more detail about housing commons on lowimpact.org. A community land trust by itself isn’t a commons, but the structure can be used to create something approximating a commons, with care to ensure the trustees are representative of multiple stakeholders, and operate democratically.

Julian Jones talked about water and sewage treatment in Stroud and Sudan, how England’s water industry is now imploding (new opportunities for water commons perhaps) and also has a an article here. Julian noted that tribalism, arising from fear of loss of resources, is a thing in the UK just as much as in North Africa (and yet there is abundance of water, it’s just badly managed). It was also interesting to meet a few folks who are witholding payment of the sewerage part of their water bills in protest at their water companies disregard of the Water Acts. It also turns out that using glyphosate can cause farmland to warm up relative to traditional farming methods – by up to 10C – and also reduces how rainwater soaks into the ground.

There’s a post-Festival effort to pin down a definition, or a framing of commoning, thanks to Joss. Comments welcome.

Commoning is a local community owning and caring for useful infrastructure that they share. It helps keep costs down (as there’s no profit being taken by some big company) and enables local people to have their say in how the infrastructure is operated. A commons can be any sort of shared infrastructure for the community – housing, energy, food, land, community spaces, gyms, workshops, cars and bikes, and more!

I was excited about the prospects for the Commons Lab, a new initiative which Chikara Shimasaki is driving, or as he said, “fearlessly exploring,” to build the support ecosystem for the commoning movement. Creating space for research and learning around commons projects, developing toolkits, and forums for sharing and connecting, seems a great way to nurture this new/newly emerging movement. The intent is to embrace multidisciplinary sciences and to operate from evidence-based approaches, learning from every available source.

Chik felt there was value in a diversity of definitions of commoning/commons, which makes sense for creating a ‘big tent’ (as long as the value isn’t diluted by different projects claiming to be commons).

Stroud has an astonishing number of commons projects (and a new website coming soon.)

I dumped my long form notes – of uncertain correctness, let alone completeness – in a google doc; additions welcome.

Thanks to everyone who helped organise the Festival! It was an inspiring and educational event.

Leave a Reply