Dil (Mutual Credit Services), Amrit and I (Stroud Commons) were invited to give a presentation at the Bath Royal Literary & Scientific Institution, about the budding commons economy, on January 9th this year.

Dil talked about the philosophy of commoning, I talked about the basic ideas behind the new ‘commoners movement’, and Amrit talked about what we’ve been getting up to in Stroud.

The event was recorded, and when it’s ready (we were told before the end of Jan), we’ll post it here.

Probably the world’s top academic on the commons, David Bollier, was in Bristol recently, and Chik and Michelle from Stroud Commons went to meet him. He introduced some people from Bristol Commons, some of whom attended the event.

In the pub afterwards, we talked with activists from Bath, who’ve already put together a core group of ‘commoners’ in Bath. Some Bristol Commons members were in the pub too, and we talked about how we might liaise to help grow the commons in the Bristol area, with a little ‘commoning triangle’ involving Bristol, Bath and Stroud Commons groups.

Here’s the transcript and slides for my part of the presentation (recording of the whole event coming soon):

Amrit and I are part of Stroud Commons. Dil’s organisation is called Mutual Credit Services – they’re producing models and designs for building the commons economy that we’re implementing in Stroud. I’m going to talk about basic commons ideas. Amrit is going to talk about what we’re up to in Stroud,

This is what I’m going to talk about:

- why I’m interested in the commons

- Elinor Ostrom’s commons principles

- new tools / ideas that could make the commons grow exponentially

- examples of these commons ideas around the world

- call to action

1. why I’m interested in the commons:

Many reasons to be interested in commons. These are mine.

My main interest is in trying to plant the seeds of a new system – this system destroys nature, democracy, community, spirituality. That’s a bad idea, in my book.

Other reasons – community building, affordability, community resilience to collapse scenarios. All v good reasons too.

We can’t vote for a new system, because of the state’s relationship with the corporate sector, and corporate ownership of the media. And the corporate sector really doesn’t want a new system.

There can’t be any ‘uprising’ or ‘overthrow’, as they’re too strong. Protest or petitioning just pings off. Co-ops and mutuals were a good attempt but they have to go into debt to obtain infrastructure, clever lawyers have managed to get around their asset locks, and they haven’t federated to build the basis of something new. They’ve been around for 150 years, and they’re not challenging the system, and they’re now they’re being swallowed by it (the Co-op Bank, Co-op Energy, most of the building societies are now owned by capitalists).

I think the commons is our best bet for the basis of a new system.

2. Ostrom’s commons principles

The kind of commons we’re trying to build are not natural ‘open access’ commons like the open ocean, the atmosphere, sunlight or rainfall, and not ‘anything to do with building community’. They’re based on the commons principles laid out by Elinor Ostrom, in Governing the Commons. She shows that communities can develop systems of self-governance to manage resources themselves – the essentials of life don’t have to be provided by the state or corporations.

There are 8 principles. If you go to stroudcommons.org/about, you can see them. To summarise:

Commons have 3 parts:

1) resources / assets – could be land, housing, energy, water or transport infrastructure, social care, broadband, leisure facilities, pubs, manufacturing – anything;

2) ‘commoners’ – local people who control and use them, and

3) a set of rules, written by the commoners, so that the resources are not lost, by being sold or used up.

3. new tools

We have the tools to build this new economy.

The key is getting investments.

What investors are putting their money into is future ‘stuff’.

Let’s use an energy commons group to illustrate this. Say they want to put up a big wind turbine, or cover 100 roofs with solar panels.

At the moment, to get the cash to do this, they have to ask for a bank loan or create a limited company and sell shares. But that’s not going to be community-owned for long. Or they can issue community shares, which are great, but usually with fixed returns lower than inflation – that’s not going to attract enough investors to form the basis of a new system.

Chris Cook is a senior research fellow at UCL, and director of Island Power, building energy commons in the Pacific. He came up with a new idea.

The group issue vouchers for what they’re going to provide in the future. In the case of the energy commons – electricity.

The vouchers will eventually be issued and recorded on an app. For now, it can be done on a spreadsheet.

They issue vouchers and sell them to investors for cash.

They use the cash to build / purchase assets – in this case, say, a wind turbine.

BUT: the vouchers are not denominated in £, they’re denominated in ‘stuff’.

So energy vouchers are denominated in kWh – ie in electricity.

Other sector commons denominate their vouchers in other things – like square metres (for housing) or veg boxes, tons of firewood, acres of land, hours of social care, cubic metres of water etc.

These investments are:

a) valuable, because you’re getting future valuable stuff, not just for today’s prices, but for a discount on today’s prices.

b) inflation-proof, because a kWh or a ton of firewood or an hour of social care etc. is the same in 20 years as it is now. Unlike a £.

c) secure – because they’re going to remain valuable as long as people want housing, food, electricity, heating, social care etc. i.e. forever.

Investors can:

a) use the vouchers themselves, in future, for the stuff they’re denominated in

b) sell the vouchers to an end-user (via the commons group – they don’t have to go out and find buyers themselves)

c) sell blocks of vouchers to other investors

d) keep them as part of their pension

So that’s the basic idea for building the commons in all sectors, except banking / money.

So in this case, rather than the future stuff vouchers, there are a couple of other tools – credit clearing and mutual credit.

Credit clearing is what the banks do with each other, to save themselves lots of money. So if it’s good enough for them, it’s good enough for us.

It works like this:

If I owe you £10, and you owe me £10, we don’t have to find £10 each to pay each other. We can just clear it.

It’s the same for a loop of 10 people, all owing the next one £10. They can just clear the lot.

But in business trading loops, businesses owe each other different amounts.

Here’s an example.

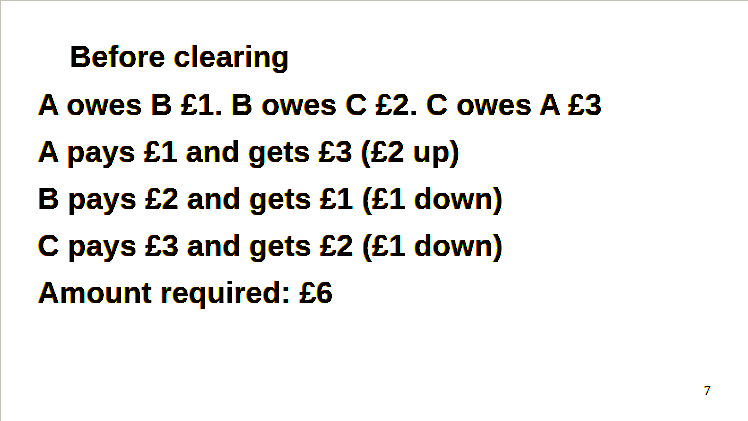

So business A owes business B £1. B owes C £2. C owes A £3. In a loop. If they all make those payments, £6 is needed. A is then £2 up, the other 2 are £1 down. Yes?

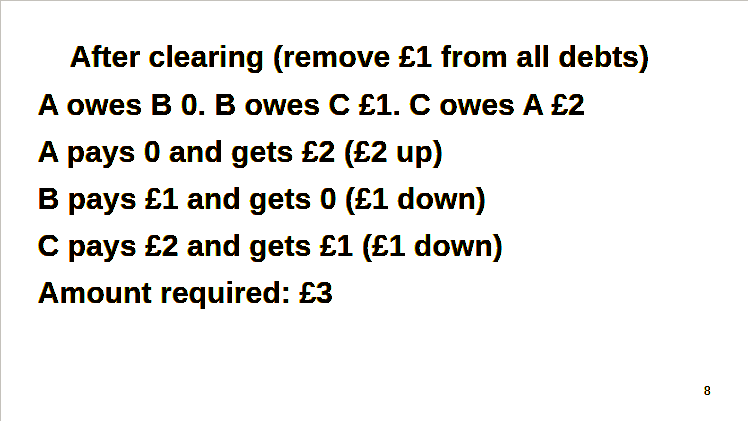

But if we first clear the lowest amount (£1) from all debts, you get to the same place.

So if we remove £1 (the lowest amount owed) from all debts, A owes B nothing. B owes C £1. C owes A £2. A is still £2 up and the other 2 are £1 down – the same as before. Yes?

But – this is the magic bit. In this case, you only need £3 to pay all the debts.

We have algorithms to find the trading loops, and automatically remove the lowest debt from all participants in each loop.

Research in Slovenia, where they’ve had a national credit clearing scheme for 30 years, shows that this kind of clearing can reduce the need for hard cash / fiat money by participating businesses by 25%!

Which reduces the need for banks, interest, payment card fees etc, and keeps more money in your community.

Then, software can display the trading loops onto a map, so you have a visual display of the local economy.

You can see clusters of businesses that trade with each other a lot.

You can approach them and offer them the next tool – mutual credit – which works if you have businesses that know and trust each other.

These regularly-trading businesses get a shared ledger, and each business has an account.

Their account starts at zero. When they sell their account goes up, when they buy it goes down. But it’s only numbers, not money.

Everyone has a positive and negative limit, decided by the group. And away you go. It’s just a moneyless accounting system, showing who’s done what for whom.

This has the potential to remove the need for banks, interest and payment card fees completely.

So credit clearing is a ‘gateway drug’ to mutual credit, if you like.

And then – more magic.

The savings vouchers, credit clearing and mutual credit trading can all be written on the ‘Credit Commons Protocol’.

A protocol is a set of rules that allows different users to interact.

For example, the rules of chess allow anyone who understands them to play chess with anyone else who understands them, wherever they come from, whatever language they speak, however old they are etc. It works for speed chess, online chess, or using giant boards with human pieces.

It means that saving vouchers can be bought and sold with mutual credit, employees of participating businesses can be paid in mutual credit etc. plus there’s credit clearing going on all the time.

It also means that commons networks in different towns can trade with each other.

It builds the foundation of a completely new, commons economy.

4. examples

In Governing the Commons, Ostrom described successful commons fisheries, forests, pasture, irrigation projects, that have been around for hundreds of years.

Credit clearing has also been around for hundreds of years. I mentioned that banks do it among themselves.

Slovenia has done it for years.

Mutual credit has been around for years too.

The International Reciprocal Trade Association is a trade body for commercial mutual credit networks around the world. They estimate that the total value of their members’ mutual credit trade is over $12 billion a year. But this is a conventional, capitalist institution. Our groups would be community-owned.

Sardex is a mutual credit network in Sardinia, with 4000 members and trades with a value of over 50 million euros annually.

Grassroots Economics is a network in Kenya (not exactly mutual credit, but similar) with 80,000 micro businesses.

The Wir Bank in Switzerland has been around since the 1930s, and trades around a billion euros in mutual credit annually.

Island Power – building energy commons in the Pacific.

MCS are working with our group in Stroud and in Liverpool, they’re building a large credit clearing network that they hope to launch this year.

They’re happy to work with other towns. They’re also working with other groups in Sweden, Norway, the US, India, and potentially Costa Rica, Nigeria and Spain.

In Stroud, we’re putting together a package for formative groups in other towns, including a template for a website, documentation, manuals, advice etc. We’ll zoom with you, or come and meet with you.

We’re talking with people in about 20 other towns, and other countries.

Contact me – via Stroud Commons. Or dave@lowimpact.org

Leave a Reply