I’d heard of friendly societies – small groups of local people who would put some money into a shared pot every week, and use it to look after families when the breadwinner was unable to work, for any reason. I thought that these little local insurance schemes were socially useful, but marginal. I was wrong. Here’s what I’ve learnt recently.

- Every neighbourhood had a friendly society. At their height, just before WW1 9 million people were members of friendly societies in the UK!

- Each society employed a doctor. (This was opposed by the medical profession, who saw this as being controlled by their ‘social inferiors’ – plus it didn’t pay enough).

- If a household hit hard times, fellow members would not only bring some money, but would also bring cooked food, provide childcare, do shopping, and anything else they might need, including a chat and a bit of company.

- Cheating wasn’t possible, as locals would know if someone was really unable to work or not.

- Friendly societies were killed in the UK with the introduction of the welfare state and NHS (both of which are now being eroded and sold to the corporate sector).

I believe that:

- Welfare states were an attempt to stave off revolution after WWII, but now the threat of revolution has abated, they’re being dismantled / sold. They were only ever for making poverty tolerable, not ending it.

- Friendly societies were and still are a better means of providing care and support for people in communities everywhere.

- We can revive and grow friendly societies in response to the erosion of a viable welfare state, as part of a new commons economy.

I interviewed Shaila Agha, of Grassroots Economics in Kenya, where there’s a network of 80,000 micro-businesses (last time I heard) trading together via a moneyless mutual credit system. I asked her why it had taken off in Kenya, but not in the West (apart from the fact that a moneyless trading scheme is obviously going to be very attractive to small businesses in areas where there’s very little money). She said it’s because we don’t have ‘chamas’ – local village saving groups, usually run by women, where money is pooled and members can withdraw cash if and when they’re in need / they want to start a business etc.

Since then I’ve spoken with my twenty-something nephew – a teacher in the Midlands, who has a shared bank account with 15 friends, for the same reason. I told him that what he was part of was a ‘chama’. I’ll blog more about his mutual aid scheme, chamas and friendly societies soon.

Meanwhile, here’s an article by Tony Parker and Jane Ferrie:

Health and welfare: rejecting the state in the status quo – examples of an Anarchist approach

And here’s an excerpt from a little book called ‘Anarchism: a very short introduction’ by Colin Ward:

“Anarchists are frequently told that their antipathy to the state is historically outmoded, since a main function of the modern state is the provision of social welfare. They respond by stressing that social welfare in Britain did not originate from government, nor from the post-war National Insurance laws, nor with the initiation of the National Health Service in 1948. It evolved from the vast network of friendly societies and mutual aid organizations that had sprung up through working-class self-help in the 19th century.

The founding father of the NHS was the then member of parliament for Tredegar in South Wales, Aneurin Bevan, the Labour Government’s Minister of Health. His constituency was the home of the Tredegar Medical Society, founded in 1870 and surviving until 1995. It provided medical care for the local employed workers, who were mostly miners and steelworkers, but also (unlike the pre-1948 National Health Insurance) for the needs of dependants, children, the old, and the non-employed: everyone living in the district. It was sustained through the years by voluntary contributions of three old pennies in the pound from the wage-packets of miners and steelworkers. At one time the society employed five doctors, a dentist, a chiropodist and a physiotherapist to care for the health of about 25,000 people.

A retired miner told Peter Hennessy that when Bevan initiated the National Health Service, ‘We thought he was turning the whole country into one big Tredegar.’ In practice, the Health Service has been in a state of continuous reorganization ever since its foundation, but has never been submitted to a local and federalized approach to medical care. A second reflection on the story of Tredegar is that when every employed worker in that town paid a voluntary levy to extend the local medical service to every resident, the earnings of even highly skilled industrial workers were below the liability to income tax. But ever since full employment and the system of PAYE (automatic deduction of tax as a duty of employers) was introduced during the Second World War, the central government’s Treasury has creamed off the cash that once supported local initiatives. If the pattern of local self-taxation on the Tredegar model had become the general pattern for health provision, this permanent daily need would not have become the plaything of central government financial policy.

Anarchists cite this little, local example of an alternative approach to the provision of health care to indicate that a different style of social organization could have evolved. In British experience, another variety was to be found in the 1930s and 1950s in what became known as the Peckham Experiment in south London, which was essentially a family health club where medical care was a feature of a social club providing sporting and swimming facilities. These and much more recent attempts to change the relationships in meeting universal social needs exemplify the urgency of the search for alternatives to the dreary polarity of public bureaucracy on the one hand and private profit on the other. I have myself heard the former chief architect to the Ministry of Health admit that the advice he gave for years on hospital design was misguided, and have heard similar confessions from management consultants, expensively hired to solve the NHS’s organizational problems.

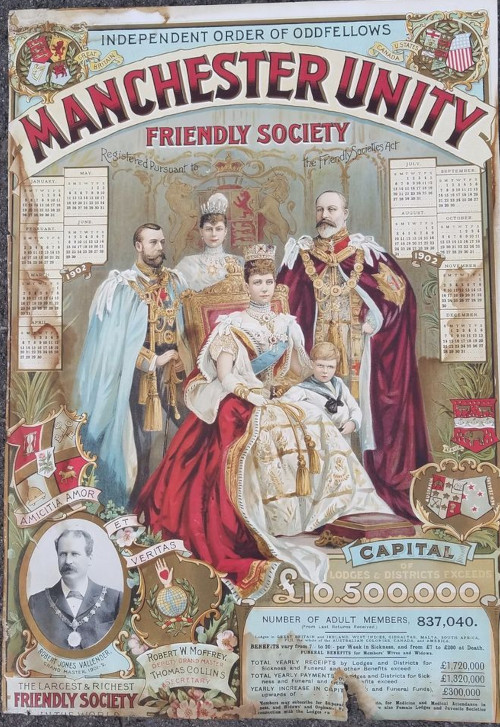

A century ago, Kropotkin noted the endless variety of ‘friendly societies, the unities of oddfellows, the village and town clubs organised for meeting the doctor’s bills’ built up by working-class self-help; as part of his evidence for Mutual Aid: A Factor ofEvolution, and in a later book, Modern Science and Anarchism, he declared that ‘the economic and political liberation of man will have to create new forms for its expression in life, instead of those established by the State’. For he saw it as self-evident that ‘this new form will have to be more popular, more decentralised, and nearer to the folk-mote self-government than representative government can ever be’. He reiterated that we will be compelled to find new forms of organization for the social functions that the state fulfils through the bureaucracy, and that ‘as long as this is not done, nothing will be done’.

It is often suggested that as a result of modern personal mobility and instant communications, we all live in a series of global villages and that consequently the concept of local control of local services is obsolete. But there is confusion here between the concepts of communities of propinquity and communities of interest. We may share concerns with people on the other side of the world, and not even know our neighbours. But the picture is transformed at different stages in our personal or family history when we have

shared interests with other users of the local primary school or health centre, and the local shop or post office. Here there is, as every parent will confirm, an intense concern with very local issues.

Alternative patterns of social control of local facilities could have emerged, but for the fact that centralized government imposed national uniformity, while popular disillusionment with the bureaucratic welfare state coincided with the rise of the all-party gospel of managerial capitalism. Anarchists claim that after the inevitable disappointment, an alternative concept of socialism will be rediscovered. They argue that the identification of social welfare with bureaucratic managerialism is one of the factors that has delayed the exploration of other approaches for half a century. The private sector, as it is called, is happy to take over the health needs of those citizens who can pay its bills. Other citizens would either have to suffer the minimal services that remain for them, or to re-create the institutions that they built up in the 19th century. The anarchists see their methods as more relevant than ever, waiting to be reinvented, precisely because modern society has learned the limitations of both socialist and capitalist alternatives.”

Leave a Reply